Voodoo Hotel Fire Tragedy

Long Read. A Haitian story, with rum interlude

Apologies to Hot Air subscribers for recent silence. I’ve been in Bulgaria. Now reflecting on what can be written about that, but in the meantime I have to react to two items of shocking news from the Caribbean. This is an autumn of obituaries, several more on the way, and right now it’s deceased buildings, two fascinating old institutions which have just disappeared.

The first is due to the slow grind of State neglect: the historic Egrem recording studio in Havana which has produced nearly a century of classic Latin music. This includes the albums of the Buena Vista Social Club series, which has incidentally acquired another new lease of spin-off life lately. The excellent substack newsletter of Judy Cantor-Navas (Cuba on Record) has just reported the famous old studio is in effect done for after years of closure, decrepitude and failed plans for renovation. I’ve visited the place many times, even taken groups of musical tourists there, so more on this shortly, in a Cuban post.

The other loss is due to more sudden and extreme circumstances. The Hotel Oloffson in Port au Prince, Haiti, was apparently burnt down in July by the gangs whose savagery has engulfed the country, in spite of the heroic attempts of an international peace keeping force - the army of Kenya, of all places - to help the failed government re-assert control.

It may seem frivolous in the desperate circumstances of Haiti to talk about pretty hotels. Indeed the owner of the Oloffson, the Haitian-American musician Richard Morse, has commented that he hardly liked to talk about his hotel in the context of so much worse horror. Nonetheless the Oloffson was a beautiful and historic place and is a great loss, and widely lamented. I stayed there in the 1990s and found it as irresistible as everybody did. The Oloffson was an outstanding example of Caribbean gingerbread style, all wood, delicate turrets, gables and verandas, adorned with fine fretwork and surrounded by lush trees overlooking a sloping tropical garden with winding drive and grand wrought iron entrance gate. Built in 1887 as a mansion for the family of Tiresias Sam, an early Haitian president, it was transformed into a hotel in 1935 by a Swedish sea captain named Oloffson, and. eventually acquired by Richard Morse who was related to a descendent of the Sam family. It was famously fictionalised as the Hotel Trianon by Graham Greene in his 1966 novel The Comedians, which opens with the body of a victim of Papa Doc Duvalier’s Ton Ton Macoutes militia found in the swimming pool.

1944 American B movie voodoo

The Oloffson’s rooms had been named after celebrities like Noel Coward, Richard Burton and Mick Jagger from Haiti’s vanished jetset heyday. By the time I got there, one room was christened Andy Kershaw, a bit of a shock: what would be next, a Noel Edmunds Suite? Morse’s father was an American academic and writer and his mother, the exquisitely named Emerante de Pradines, a Haitian dancer and folklorist. Morse and his wife Lunise turned the hotel into a meeting place for artists and musicians where RAM, the voodoo-rock band they set up, played on Thursday nights. The musical aspects of Voodoo (vodoun in Haitian Creole) are complex, on a spectrum ranging from full liturgical drum and chant sequences invoking spirit possession and trance to more or less accurate and authentic entertainment simulacra.

I visited Haiti partly to report on this fascinating phenomenon: see my article for the Independent, still relevant.

https://www.independent.co.uk/news/arts-let-the-ceremony-begin-1162419.html

Voodoo rock, as typified by bands like RAM and Boukman Eksperyans, is entertainment, but with a political/cultural message - it’s related to the rasin (racines or roots) movement, and distinct from the purely tourist voodoo shows. RAM were - they’ve just disbanded - dynamic, colourful, moderately exciting, and their shows pulled in a jovial crowd, a mix of Bohemian artist types, visiting journalists, NGO and embassy people, and plenty of assorted locals. I remember observing the reception desk down by the front gate where arriving guests checked in their guns to be placed in a big wooden chest till they left - one man discharged his pistol into the undergrowth before handing it over. I also remember the lovely big airy bedroom with huge hardwood plank floors to retire to afterwards and the excellent rum sours on the terrace, a thoroughly idyllic setting.

The rum was courtesy of Barbancourt, Haiti’s leading rum producer, and if this sounds like a bit of sponsored content edging in, I can assure you that it’s not. Chance would be a fine thing.

Barbancourt, founded by a Charentais wine merchant in the nineteenth century has recently weathered a classic dynastic succession struggle, won by Delphine Gardere, a Paris and Atlanta educated business admin professional and fifth generation descendant of the company’s founder. In 2010 the firm was hit by the devastating earthquake, and since the takeover of the gangs its employees have been kidnapped and the roads and shipping lanes cut off, though the company has succeeded in maintaining international deliveries by pre-positioning extra stocks with their distributors to cover shortfalls. Last year the company suffered its own version of the Oloffson fire, when a swathe of the canefields around the domaine were set alight, occasioning a pause in the water and health facilities Barbancourt supplies to the four hundred small cane growers they buy their ingredients from.

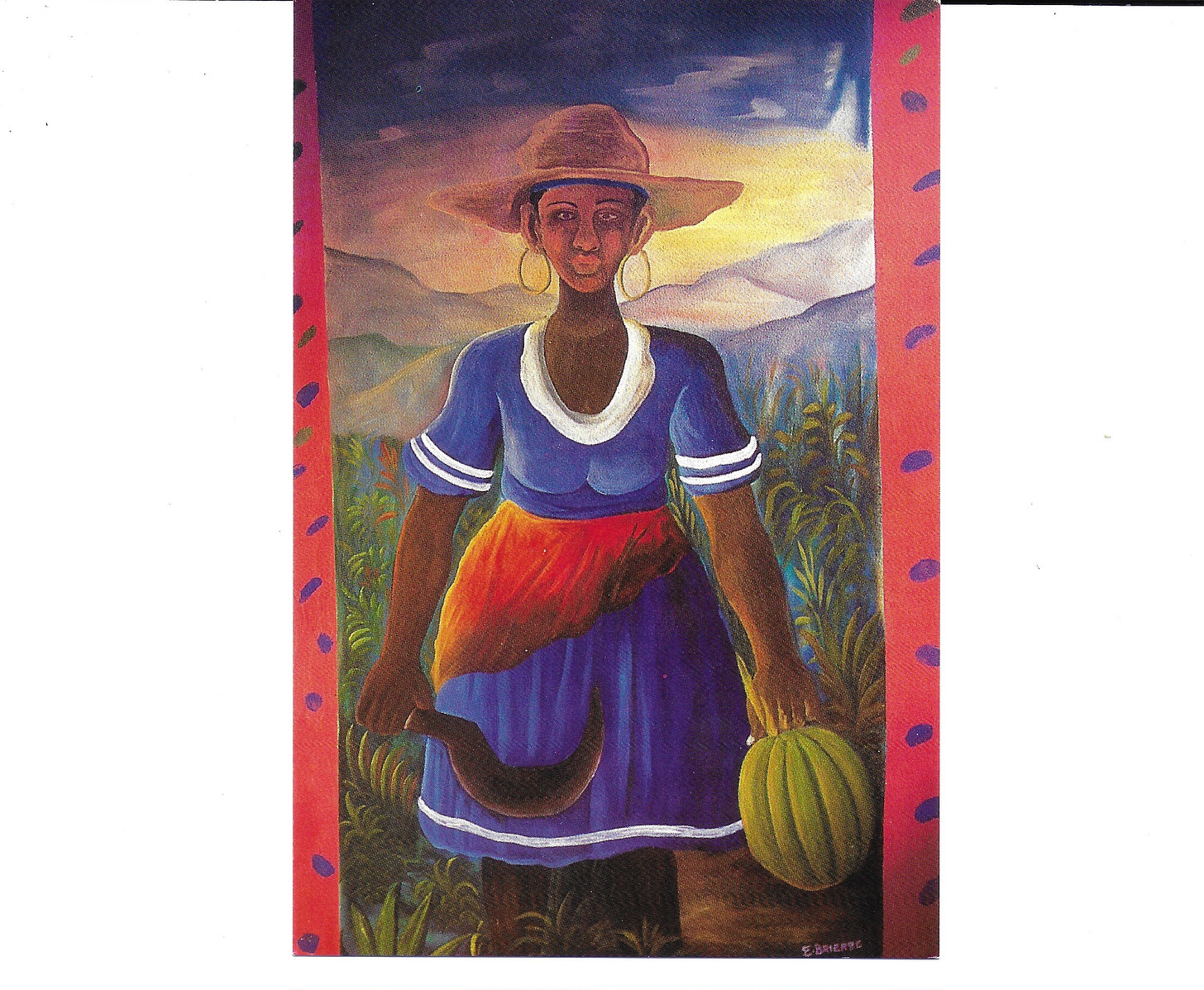

Does it seem bad taste to mention cocktail recipes at this juncture? Probably, but I reckon we need a drink. Barbancourt is close in style to a French origin rhum agricole, made from pure cane juice rather than molasses, but smoother and less funky than some, so you can just make a Martinique style ti-ponch, in effect a French daiquiri, with rum, sugar and lime. But a Rum Sour is pretty irresistible: rum, orange liqueur, lemon juice, sugar cane juice, Angostora bitters. Or there’s a Champs de Mars on the Barbancourt website, involving Maraschino liqueur, grenadine and lime juice which is pretty tasty. With a plate of little bits of spicy barbecued goat or some conch fritters. While muttering as toast an incantation to Azaka, the voodoo loa (deity) of agriculture and harvests, who features on the Barbancourt logo in slightly glamorized form. (See alternative version, from the Tap Tap Haitian restaurant in Miami, further down).

Like all great rum enterprises - think of the Bacardis - Barbancourt has a complicated genealogical structure, with marriages bringing new names into the boardrooms. The company now named Barbancourt, and founded in 1862 by Dupre Barbancourt, has been run for generations by the Garderes, while another company, Berling, based on a marque supposedly founded by a Louis Barbancourt a century earlier, and run by a another descendent of the Barbancourts, markets a brand called Vieux Labbe, named after a mid-period Labbe Barbancourt. And while Barbancourt itself operates from a new complex in the area of Cul de Sac beyond the airport, Vieux Labbe was, until the great earthquake, made in a rather remarkable antique-filled faux Norman granite chateau in the hills above Port au Prince called Jane Barbancourt’s Castle.

I called there on a jaunt north to Cap Haiten to visit the even more extraordinary and colossal Citadelle fortress built in 1830 by the briefly self-crowned Henri Christophe, King of the newly freed ex-slave nation. It’s around this area, to spoil readers’ innocent enjoyment of the cocktails, where the plantations of bitter oranges were at that time harvested and peeled in primitive and scandalously lowly paid conditions for the zest used in both Grand Marnier and Cointreau. Barbancourt claim to be dutiful employers, running a free clinic and other facilities for their work force, though the violence and the fire interrupted this operation. Think we’d better move on, or we’ll be needing to open another bottle.

More hotels, and music…Back in the capital, I moved up the hill from the Oloffson to Petionville, the Hampstead of Port au Prince, to the faintly Hollywoodian El Rancho hotel, on the advice of the Los Angeles Times correspondent who preferred it because you can see the airport road below in case of urgent need to get out. El Rancho, subsequently destroyed in the earthquake and now corporately rebuilt minus its period charisma, was another very Haitian story. The building had started life as the home of the extended family of a pennyless adventurer and gambler from Livorno who used a rapidly accumulated 1940s textile fortune to acquire the magnificent villa, plus a Rolls Royce Silver Wraith and two Lamborghinis, before ceding the place as hotel to a brother of one of Papa Doc’s generals.

In the Rancho casino I caught an excellent set by Sweet Micky, the band of a singer named Michel Martelly, an exponent of Haiti’s irresistible compas dance music, not up with the greats like Tabou Combo, but very boisterous and danceable. Martelly, generally regarded as an intimate of the ruling military/elite, went on to join the showbiz politician tendency and become Haiti’s president between 2011 and 2018. He now lives between Port au Prince and Miami, where he was sanctioned last year by the US State Department for contributing to the narcotics trafficking, corruption and violence which subsequently reached its present day paroxysm. Just as the tyrannical Papa Doc Duvalier’s favourite compas musicians, typified by Gesner Henry, known as Coupe Cloue, were the best of the period crop, so Sweet Micky was preferable in my book, on purely musical grounds, to his polar opposite politically, the leftist protest singer Manno Charlemagne, a sort of Creole Georges Brassens, ally of the liberation theologist priest and democratic president Jean Bertrand Aristide. Illustrating once again the old adage about the devil and the best tunes.

The former President back in showbiz action. No, it’s not Barack Obama

Whether the devil’s music is still the best in Haiti depends on taste. Currently the style in favour with Haitian street youth, which includes young gang members, is raboday, a bizarre mixture of percussion from the voodoo-linked rara carnival bands, cheap home synthesizers, electronic cheeps and squeaks, sections of rapping and garbled repetitive phrases, some in speeded up Mickey Mouse voices. Smallish doses of raboday can be rather compelling. For my tastes, that is: teenage Haitian gang members presumably favour largish, if not incessant, doses. What the Kenyan soldiers make of raboday is anybody’s guess. To help them out, the Haitian security forces have apparently started using drones to blow up gangsters, an idea which is reported to have produced a slight lull in gang terror. Though this may be simply a pause while the gangs get their own explosive drones from Amazon.

One odd detail from my last Haiti trip long ago lodged in my mind, perhaps less odd in view of the pyromania catalogued above. Leaving Port au Prince by coach for the Dominican Republic, passengers had to disembark at the border and have their luggage searched. The vigilance of the Customs officer checking mine wasn’t directed towards cocaine or bottles of Barbancourt or wads of dollars. His only question was: are you importing any matches?

SOUNDTRACK

I haven’t attempted to put up exhaustive set of tracks from article, just a few relevant items I like. Plenty of material online, including voodoo ritual music.

1. The great Coupe Cloue

2 and 3. Two tracks from excellent 2023 album by singer/producer Wesli, based in large Haitian diaspora centre of Montreal, the first using traditional percussion and voices, the second in the old twoubadou compas style.

4. A spot of raboday weirdness to bring us up to date from Raboday Lakay and Raboday Panda, who I’m given to understand are well known practitioners, M’lud.

With you on the raboday. Small doses but I love the Makonay track